Screenplay blocking is one of those thing your script just must get right. Otherwise, the script reader gets lost and can’t picture where characters are in physical space, and/or relative to each other in the scene you’ve written. (Read the pages to the script we’re giving script notes for below: Perfect Moonshine by A. Moreno)

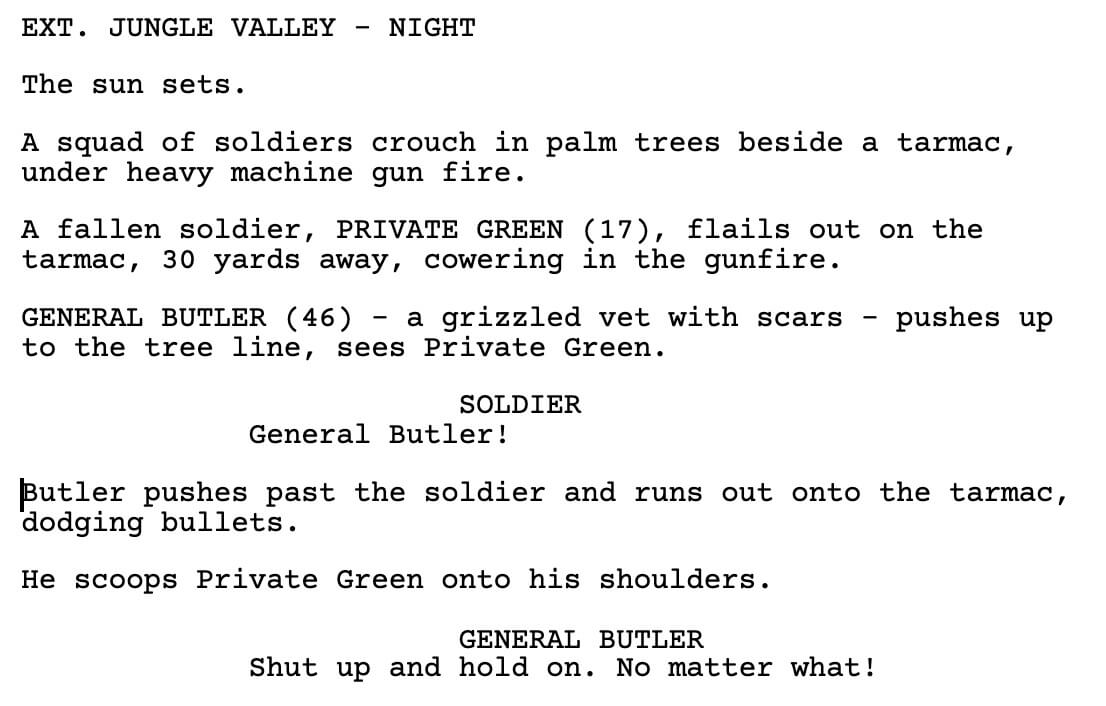

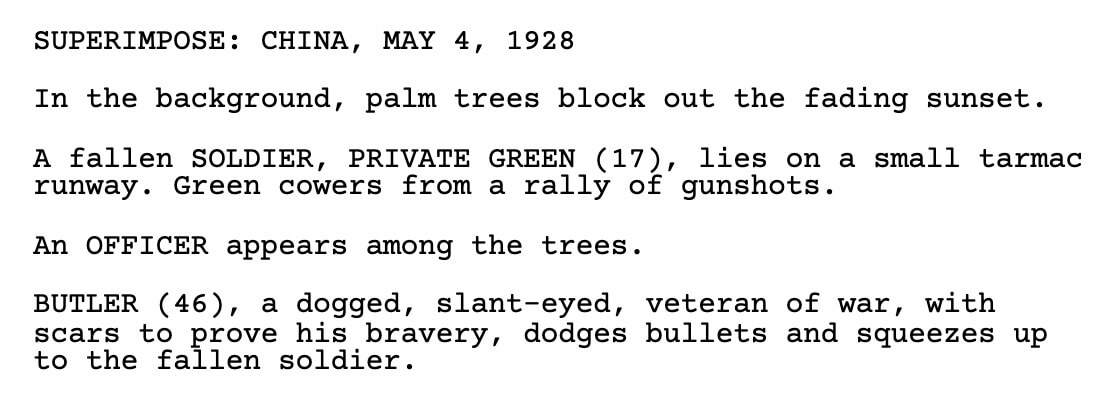

The opening beat of General Butler running out to save Private Green runs the risk of being unclear. This has mainly to do with the fact that we haven’t established the scene in the reader’s mind as well as we could.

The problem is one of visualization. We can’t quite visualize what’s going on until later down the page, and even then, you run the risk of forcing the reader to re-read what they’ve just read.

The problem lies mostly with positioning.

That is, where is Butler, relative to Green? Where are the trees, exactly?

Further complicating the ease of visualization are the “palm trees, blocking out the sunset.” This reads as “the scene takes place at sunset,” and yet goes against the slug, in which you indicate “night time.”

Even further complicating the scene is a random soldier ordering General Butler to stand down. It’s a bit of a speedbump because it reads as (a) a simple enlisted man giving orders to a General, and (b) as a general rushing out to save a soldier, when it seems more congruent to have the exact opposite.

Inverting a paradigm is great. It’s what many a strong movie concept is rooted in. Inverting a paradigm within the first few lines of your first page doesn’t quite work. The script needs to ease us in, then flip the script, so to speak.

It’s absolutely key that each line of a script is not only essential to the visualization of the film, but that it doesn’t cause confusion, or contribute to cumulative confusion. Each line needs to be *crystal clear*, and needs to contribute to an overall crystal clarity of the beat, scene, and sequence.

Don’t get me wrong. I get what you’re going for here with this beat, but only after a couple of re-reads, and going up and back through the beat a few times. Your script won’t be circular filed for one or two beats like this, and may even strike gold despite a script full of these moments, as many scripts surely have, but too many moments that are difficult for a reader to visualize easily can add up to a negative reading experience for the reader, and severely hurt your spec script’s prospects.

Here might be a better way:

There’s a similar problem with the Mercenaries and the Marines reaching the machine gun beat, because we’re not sure who the Mercenaries are. For absolute clarity, change my previous line above to:

Watch out for typos like “hanger” when you mean “hangar.”

Too much verbal exposition

From page 3:

This line is way too much verbal exposition, and that’s not a good thing for most script readers. If we absolutely *need* to find out that Commanding General Simmons headed back to the carrier, Butler was getting bored, and didn’t have much to do, because all those things are *vital* to your script, then convey that information by showing us, not telling us.

Further, the above line by Butler is a wasted moment to get the audience liking this guy. We like him when he saves the soldier etc. Now let’s see who he is as a *character*. Don’t waste moments like this. Here’s a rough idea of what I mean by using the opportunity to show character, rather than exposition:

The rest of the pages are solid, but still suffer a bit from heavy exposition. Make sure each element you’re conveying is absolutely mandatory. Favor readability, entertainment, brevity, and audience clarity over making sure the reader and audience fully grasp the historical accuracy and detail you’ve obviously taken great effort to present.