If you’re a cynical screenwriter, like me, it’s not merely recommended that you watch all 3 seasons of PBS’ post-Edwardian period drama, Downton Abbey…

…it’s utterly essential.

Especially in today’s over-sexed, over-crimed, lowest-common-denominator TV viewing environment.

(This article doesn’t give away any plot points or spoilers, so don’t worry.)

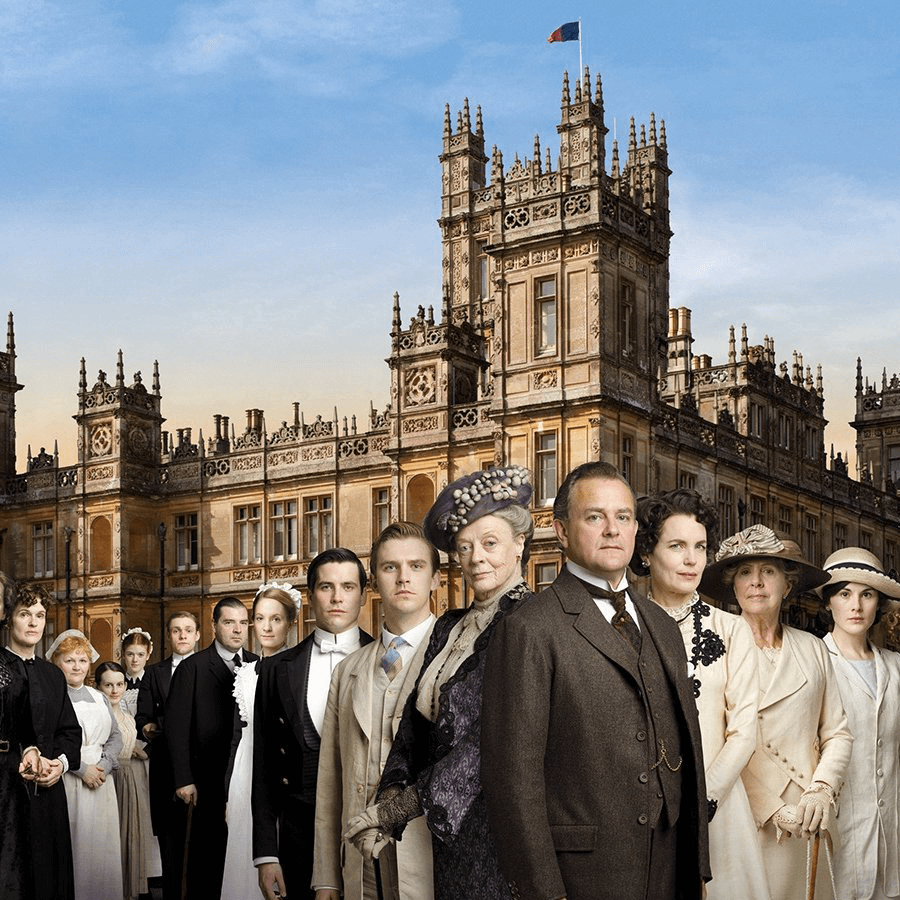

Downton Abbey starts in the post-Edwardian era in rural England, (right around the time of the sinking of the Titanic) and follows the ups, downs, dinner suits, and soup spoons of an English aristocrat and his family, and the servants who work for them.

Sounds boring, right? A stiff shirt of a show. A fluffy, false tea party we’ve seen a million times in the form of Brideshead Revisited, Upstairs/Downstairs, or even films like Gosford Park, right?

Sure. To the cynical screenwriter.

It certainly looked to me, on the surface, like something I very, very much did not want to watch.

But remember that scene in James Cameron’s The Abyss (1989), where the character is submerged in that gooey purple oxygenated gel, and told to breathe it in, because it was the only thing that would allow them to breathe and to prevent their lungs from imploding at such deep sea depths? And the guy was telling the character: trust me?

Well, trust me. That oxygenated gel is Downton Abbey.

Here are a few things screenwriters can learn from putting down their cynical goggles and picking up a typical Downton Abbey script.

Audiences occasionally need a break from reality, vampires, and ladycops

How many Ikea bowls full of pasta have you hurled at your tv screen each time a major network puts out a new reality show about fat people crying? Or a celebrity panel of judges scratching each others’ eyes out? Or another show about sexy ladycops who back-engineer homicides with their good looks, hip badges, and obligatory over-stylized flashbacks?

The average American, sure, they’re dumb. And there are a lot of them.

But believe it or not, they’re sick of that crap too. They just don’t know it.

Like chubby dumb swine, they eat whatever the farmer throws in the trough, whether it’s The Voice, or Honey-Boo-Boo, or another permutation of Honey, Which of These Three Houses Should We Buy?

Downton Abbey, at the time of this article’s writing, is really the only show on tv in its genre.

And I don’t mean early-20th century period piece. And I don’t mean long-form television. I mean it’s the only show right now (that I’m aware of at least), that’s actually eschewing cynicism, while early every other show on the air embraces, if not embodies cynicism.

And in a way, it’s almost easy for Downton, because it’s hard to imagine a show so focused on the early 20th century, a period of great faith in new technologies, and the rise of the individual, amongst other huge social movements, without being drenched in earnestness and optimism.

Screenwriters: Downton Abbey makes it okay to be earnest again. And there’s an importance to that, I hear.

You don’t need to write Lawrence of Arabia to have scope

I recently watched the most recent season, Season 3, and was surprised to see Downton Abbey, the main house/castle where everything takes place, from a few wider, more beautiful angles than I had seen in previous seasons.

I suspect it’s because the show’s funding went up in parallel with its amazing reception, but it made me realize:

I was way into the show long before those wider, sweeping shots of the castle and its surrounds; long before their wider, more well-funded(?) vistas and scenes.

I was still caught up in the scope of the show, and of its sweeping events – the Titanic, the Spanish Flu, the struggle for the Irish Free state, all of which help frame and steer the show – without having to see all of that.

Because I saw it through the lens of Lord Grantham’s family, and through the lens of Mr. Carson the Butler, and Mrs. Padmore The Chef, and Daisy, and all the other servants.

See, what I realized was – there’s sand dunes and Cinemascope…

…and then there’s the view of world events through the eyes of interesting characters who may be far, far removed from the events themselves, but still feel what it’s like to live through the events, and can transmit that feeling to audience, sometimes far better than the sweeping vistas can.

Quick, happy resolutions are really the most fantastic of fantasies

Take a look at what’s on TV. Cable, network – it doesn’t matter. Most of it, I think you’ll find, is pretty fantastical.

Fairy tales in a modern era, vampires, fat people working hard to get skinny, inner-city nobody becoming the next worldwide pop sensation…

All of them are rooted in some sort of fantasy.

And of course, that’s fine. That’s the business we’re in – entertainment. We all want to put on a show that makes people laugh, cry, run to the bathroom, whatever.

But Downton Abbey has a much different tack on the fantasy thing; on the wish-fulfillment thing.

Their plotlines and conflicts, while not about murder, greed, backstabbing, catfights, or any of the other sensationalist tropes that dominate modern television, are able to wrap themselves up relatively quickly, and relatively neatly.

What’s that, you say?

Problems… That are solved relatively quickly?

Conflict… That’s wrapped up…. “neatly?”

A hallmark of Downton, without giving anything away, seems to be: Lord of the house says “No, we can’t do that. It’s not proper.”

Then his family or outside forces work on him, and, being the gentle heart Lord Grantham is, he relents, and the problem gets wrapped up in an episode or two.

Artistically, cynically, I chafed at that. Initially.

“It’s not how life works!” “It’s lazy screenwriting!”

But after I took off my Che Guevara beanie, and my artists’ smock, I realized that what Downton was doing was actually far from lazy screenwriting.

It was actually genius because that sort of conflict writing is so counter to nearly every show in the marketplace.

That is, I submit to you, gentle screenwriter, that at the core of Downton Abbey’s success in reaching an audience lies foremost with its steering clear of sensationalist, Pretty Little Liars/Melrose Place /CSI Miami tropes, and portraying a world where conflict can be quiet, but just as powerful.

But more than that – where conflict can be wrapped up quickly, and neatly.

What greater fantasy is there to average, working class tv viewers, but to see all your problems solved, quickly and neatly?

And while wearing such fabulous clothes.

The setting, the beauty, the simplicity of the era – all of those don’t hurt. But any dumbo with a copy of Final Draft can write setting and beauty and simplicity of an era.

It takes a master screenwriter to write quiet conflict, and a master producer to guess that audiences are ready for a good dose of it.

If you want to learn how to become a master screenwriter, as we all do – stop clenching your pearls and add this show to your must-watch list.

You need a break from your cynicism.

Not to be cynical, but it’s a period piece – akin to the bubonic plague to American producers, or readers opinions of what is “marketable”. I have a period script which received a “strong consider” from your very own readers, but I cannot get an agent, or production company, even my own manager to read it!

You’re probably right, Ricki. Although America has been known to take all the best, most profitable ideas from the UK and turn them into American bastard shows, so who knows what’s in store for period specs getting produced in the US?