Tom is attractive. Beatrice is beautiful. Their dentist is gorgeous. Their mail-carrier is a MILF. Having read hundreds of scripts in my career as a script reader, I’ve encountered these sentences and many others like them. In the world according to screenwriters, the universe is an attractive place. Unfortunately, in many scripts, that’s all the universe is: a collection of attractive people running around and bumping into each other.

Many of these attractive people are female, regardless of the writer’s gender identity. Male characters are “confident” and “intelligent” while a woman is “pretty”, “attractive, despite her age”, or, in that most cringeworthy trope, “beautiful but doesn’t know it”. There is, of course, something inherently problematic in reducing people to their physical appearance in the real world, so we shouldn’t accept it in the fictional one. But from a writing standpoint, it’s especially unhelpful. Creating a good description helps us define our characters for the reader, which is the first step towards bringing them to life.

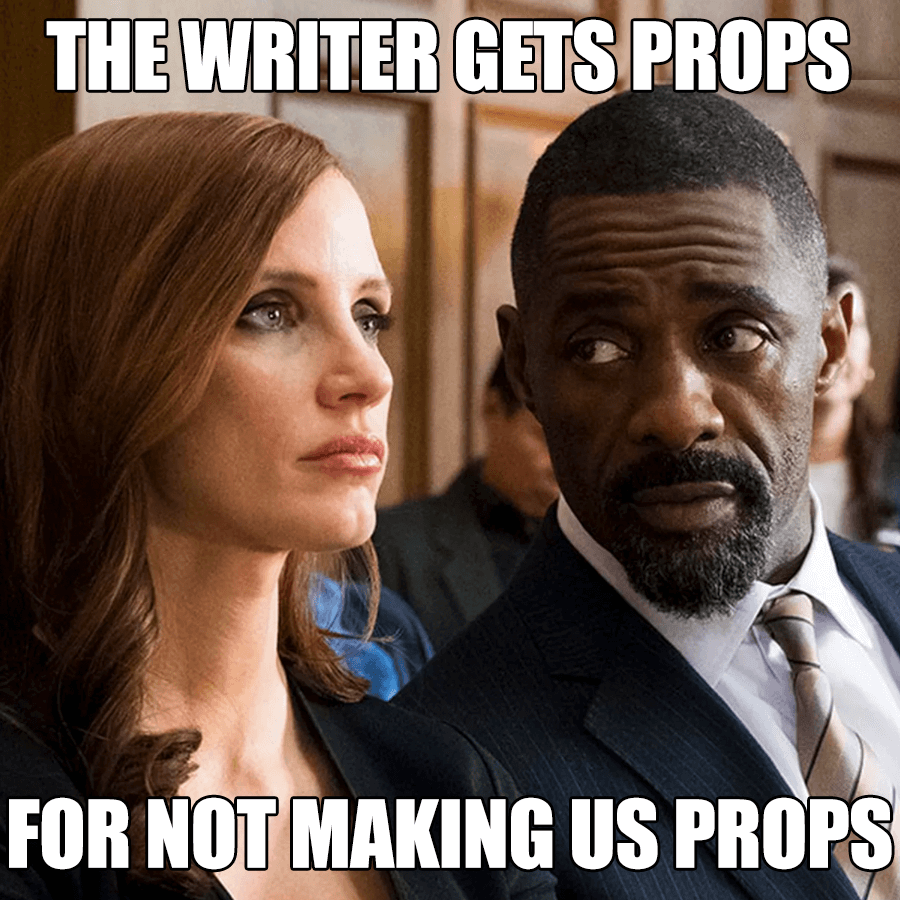

When we say only that a character is attractive, it doesn’t help the reader figure out who these people are or what makes them interesting. Paintings are attractive. So are constellations, flowers, and antique ceramic urns. These things are also inert and would make terrible protagonists. Reducing someone to their beauty diminishes them into props. Props are useful in drama – every story has them – but they aren’t what keeps us engaged. A good-looking character might catch our eye, but they aren’t going to be why we stick around.

Oscar nominee Emerald Ferrell offers great descriptions in the script for Promising Young Woman. Jez is a “shy sweet guy” while Paul is a “sweaty Alpha bro whose super fragile masculinity is always one rejection away from being shattered to pieces.” When we meet Cassandra, our protagonist, she’s “hammered” with “her hair plastered to her face, mascara under her glazed eyes.” Anyone who’s seen the trailer for Promising Young Woman can tell you this outward facade is an act. When Cassandra is next described, she is “remorseless, calm, and, honestly, pretty cool.”

It is true, of course, that people who adhere to society’s standard of beauty often find it easier to get by in certain situations and one of these situations might be in our script. And, obviously, whenever sex and love enter the story, it’s often easier if the people involved are attracted to each other. In Promising Young Woman, Jez clearly finds Cassandra attractive — the script even tells us he thinks she’s “really pretty” as he wonders if he has a chance with her. However, beauty isn’t Cassandra’s only defining trait.

At one point, Cassandra dresses up so she “looks hot in a highlighted, feather-eyed, Instagram way.” The fact that Cassandra is pretty isn’t important. What’s important is that she’s presenting herself in accordance with society’s expectations. Cassandra is playing at being pretty. Why? Therein lies the tale.

If our characters are going to be attractive, we need to think about how they use that attractiveness and what they have to do to maintain it. The reason telling us someone is “beautiful but doesn’t know it” is ineffective is because this doesn’t give us any important information. It tells us something the character doesn’t know, but this isn’t going to be useful to the actor. An actor can’t play ignorance. Suppose the screenwriter wrote “thinks they’re ugly and dresses like they want to be ignored”. This tells us something important.

Beauty can’t be a passive trait. It’s perceived presence or perceived absence has to say something about who the character is and how they want the world to see them.

In Blackkklansman by Charlie Wachtel and David Rabinowitz, Ron Stallworth sees Patrice and is “taken by her Beauty”. But we’re also told Patrice is in a “hip array of militant wear” and that she’s watching the door, where she’s “clearly in charge”. In a few lines, a lot of important information is conveyed. We know that Ron is interested in her but we also get a good sense of what kind of character Patrice is and how she presents herself to the world.

When we first get a good look at Molly in Molly’s Game, Aaron Sorkin tells us she “still has her athlete’s body”. This is an important character note given that, in the first five minutes, we learned Molly was a skiing protege who suffered an injury. The fact she’s still in shape tells us something important about her. If Molly had been dumpy and out of shape, that would have told us something too.

Every adjective is a clue. Every description is an opportunity to keep telling the story.

If we only had one adjective to describe our protagonists, it would be a waste to use it on the word “attractive”. If our movie is being made, it will probably feature actors and (spoiler alert) actors are generally attractive people. We can assume the cast will be made up of some good-looking thespians. When choosing descriptions for the main characters, it’s always better to choose words that either describe the characters’ personality or provide descriptions that reflect their inner world.

In Rian Johnson’s Knives Out, Linda is “60ish, well put together, sharp and steely eyed” who “dresses and speaks with a little more sharpness than any situation she’s in requires.” In Greta Gerwig’s Little Women, Laurie is “a 26-year-old without a sense of direction.” In Promising Young Woman, Madison is “gorgeous”, but Ferrell also informs us that she’s “one of those people who has a way of making every compliment sound like a burn”.

Aside from being concise and vivid, these descriptions offer something unique. Every specific choice we make as writers takes us one step closer to ensuring the final product matches the ideas in our heads. The screenplay is just the first stage in the long march to production and the more specific we are about our intentions, the more specific the casting becomes. A good description tells the director how these characters should be presented. They tell the casting agent what type of person should be brought in to the audition room. And they tell the actor how the characters should be played.

In any script, characters exist in two dimensions. It takes a team of people to bring them to life. What is the best way to do it? When asking this question, people will look to our scripts. We need to make sure the answer is there.