The two most popular screenwriting software packages – Movie Magic Screenwriter and Final Draft – are popular for many reasons:

Formatting your script as you go by simply hitting the TAB key… allowing screenwriters to customize the look and feel of their screenplays… built-in index cards and scene navigation and other writing aids…

Not to mention the slew of features that each of these venerable screenwriting suites have crammed into their software over the decades they’ve been in business: colored pages and revisions, watermarking, page count cheating, dual dialogue, text-to-speech, you name it.

But when it comes down to it, both of these major apps — Final Draft and Movie Magic Screenwriter — come up short in at least one key category:

The future.

In 1999, I began work on an original screenplay of mine. I never finished. Because it was bad.

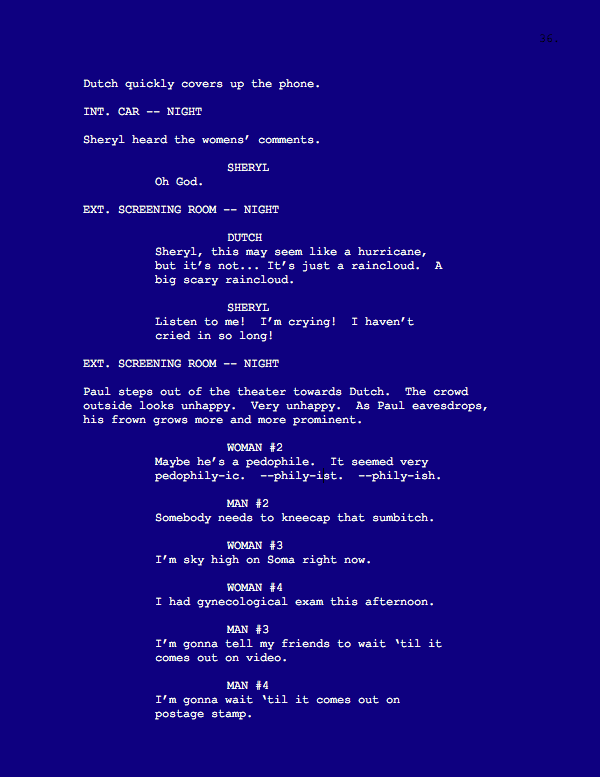

But today, I opened the draft I’d started on, dated October 1999, using Final Draft 9. And it looks exactly as I left it. Down to the choice of the colors. (Back then I set the background of my scripts to blue and the text to white, as I believed it was easier on the eyes.)

Quality of the writing notwithstanding, my screenplay from 15 years ago opened perfectly, and was able to edit it just fine.

And I did the same for a script that I converted to Movie Magic Screenwriter in 2003. The script opened just fine in Movie Magic Screenwriter this morning, and I could pick up exactly where I left off, should I ever feel the need to bask in my lackluster screenwriting skills from the previous decade.

But what about the future 15 years? Will I still be able to open these files?

What if these companies go out of business? There’s no sign of that happening now, but who knows what the future holds?

What if Movie Magic Screenwriter or Final Draft change drastically? Or vanish?

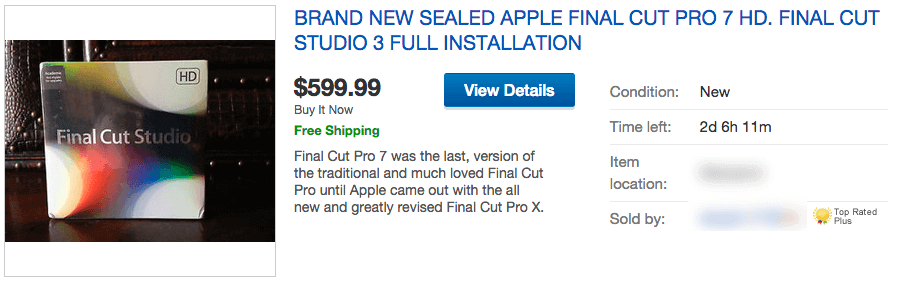

Unlikely. But, if you’re anywhere near the post-production sphere of the film industry you might remember a few years back, when Apple replaced their extremely popular, extremely functional, extremely professional editing app Final Cut with what some would argue was a dumbed-down consumer version of the app called Final Cut X.

Fans of the original program freaked out. A huge swath of them switched to other options, like Adobe Premiere, swearing off Apple software completely.

To be fair, many loved the new iteration of Final Cut, and Apple has worked hard to replace a lot of the professional features that users complained were gutted when they made the jump to Final Cut X.

But the new Final Cut X didn’t natively open any of the project files that users had created in Final Cut 7 or previous versions, causing a great deal of frustration and technical jumping-through-hoops for many editors trying to get their projects to open in the new version.

In short, Apple ended a very popular app, stopped selling it, and stopped supporting it, and replaced it with a completely different newer version, and that left a lot of people high and dry, and angry.

As a result, copies of the old Final Cut, especially its lower-priced upgrade-only versions, started showing up on eBay. With some pretty egregious price tags attached. Apple basically created a black market for their old software.

Could that specific sort of thing happen with an app like Movie Magic Screenwriter or Final Draft?

It’s possible, but I’d say extremely unlikely. Screenwriting apps are a lot less complex than full-featured post production packages, and companies who put them out know how important is the issue of backwards compatibility when it comes to script files, so we can safely bet that any future iteration of Final Draft or Screenwriter will include the ability to open all your old scripts just fine.

More Likely: The Screenwriting App Absorption Scenario

What’s more possible is that one of these two big companies gets absorbed into the other one, and the “winner” squeezes all the users of the “loser’s” software towards using the “winner’s” file format.

To be clear, I don’t think that squeeze would take place immediately, or even directly, for example, in the form of the “winner” company saying “Alright screenwriters. Move all your scripts to our new platform or else.”

More likely, the “winner” company would likely make the “loser” file format easy to open or import.

But over time, we’d likely see that old “loser” format using less and less in the screenwriting space. After all, the software has been bought out by the bigger “winner” company, so who’s using the “loser” software except for the diehards?

And how long will the diehards be able to use that old software if the old company isn’t around anymore to support it, update it, keep it free from bugs and security issues, and what not? You can bet that the “winner” company who bought out that “loser” company isn’t going to be providing patches, updates, and support for the software they bought out.

So with just one of the two big boys of the screenwriting software space now the top dog, your script files, old and new — all of that hard work, all of those great ideas and funny scenes and touching cinematic moments you bled for over your keyboard for so many years — all of that is now subject to the whims of a single software company.

Will their app let you open your files today? Sure. Will that app be around in 20 years? That, mi amigo, es la pregunta.

So how do you “future-proof” your screenplays?

There’s two main methods I recommend:

Use a screenwriting app with an open, non-binary file format

Movie Magic Screenwriter and Final Draft both employ what’s called a “binary” file format to “enclose” their script files.

Whenever you write a script in one of these apps, and the app saves it to disk, your script gets “enclosed” within a proprietary set of code. Think of it as your script getting “encoded” and the only way to “decode” it is to open the script file with the app that you created and save it in.

The motivation behind that sort of thinking on the part of the screenwriting companies makes sense, to some extent, but more so in the earlier days of the personal computing revolution and again in the epoch of the nascent internet.

Really the only way to create any sort of user-generated document using a professional software suite and to build a company and a user base was to go proprietary. Binary. Control the document/file that the user generated and you control the experience. And it was primarily a retail experience: you go to a store, buy the software on a CD or disks, you install the software on your machine.

By controlling the experience, you can, rightly so, generate revenue and a base of loyal customers. This is how Final Draft and Screenwriter basically did it, and a few others which now line the annals of screenwriting app history.

Think Microsoft Word. Excel. Those files, for pretty much the first 20 years of their existence, didn’t open anywhere but Microsoft Office. It’s only recently that they’ve become usable with a handful of non-Microsoft third-party apps.

But then a funny thing happened on the way to the world wide web: talented software developers, large and small, were suddenly able to reach customers directly, via the web. And the screenwriting app market opened up significantly.

And one of the best results to come from the “new bloom” of screenwriting app technology over the last few years has been the concept of the non-binary screenplay file format.

Example: The app Fade In uses the Open Screenplay Format (OSF) and the app Highland uses the Fountain markup language, both XML-based and readable by not just those two programs, respectively, but by any piece of software that can open and read text files. Apps, web browsers, word processors, simple text editors, pretty much you name it and the files that you create in these formats can be opened in it.

My opinion? This is the 21st century. Being able to open your screenplay file doesn’t have to be dependent on paying for any specific software. What you write in software suite A should be openable in software suite B. (Not to mention, what app you choose to write your screenplays with should be a decision you make based on the quality of the app itself, not the question of how many other people are using that particular app.)

Keep install files of your closed, binary screenwriting apps

If you’d like to stick to your binary script file and your Screenwriter or Final Draft, by all means, please do. I’ve used Final Draft and Screenwriter extensively, and probably will continue to do so, even as I gravitate towards other apps like Fade In.

One way to hedge your bets when it comes to ensuring backwards compatibility is to keep an archive of every install file.

That is, if you’ve purchased Final Draft 8 on disk, keep the disk. If you upgraded to Final Draft 9 and it’s asking you to download and install a new update, go for it, but save that downloaded update file in a separate directory you can use later.

In short, keep all of your install files so that you can, at any time in the future, reinstall a version of that particular app in order to access your files, should the need ever arise. And again, keep in mind, I think it’s highly unlikely that any of the major software companies that employ binary file formats are going to ever be tempted to leave their users high and dry when it comes to backwards compatibility, but the fact is: you never know what could happen, and I for one don’t want to risk it.

And by the way, if you’re planning on keeping an archive of install files/disks for every iteration of Final Draft or Movie Magic Screenwriter or any other binary-based writing app, you might want to also keep an archive of OS install disks/files handy as well. That version of Screenwriter you’ve archived that was designed to work in Windows XP might not work so well in Windows 21 in the year 2050.

Trees, baby, trees

And while it’s not exactly future-proofing, I’d be remiss if I didn’t suggest getting your work down onto the printed page. Files are zeroes and ones, and they can be corrupted via age, magnets, heat, and light. Out of that list, paper is pretty much only immune to magnets, but a printed script remains an essential part of future-proofing/protecting your screenwriting.

Not to mention, as OCR (Optical Character Recognition) improves, so do your chances of importing an entire printed script into whatever screenwriting app your future self downloads off of the Mars colony internet in 2077.