Writing dialogue is easy. Writing strong dialogue — dialogue which an audience will consider authentic-sounding and believable — is an entirely different skill, and one that all screenwriters must have if they hope to write successful screenplays and teleplays.

The first step in learning to write strong, authentic dialogue begins with listening. Listening to real conversations in real life between / among real people.

Paying close attention to those conversations, the astute screenwriter will notice several key common traits of all human dialogue.

Fragment your sentences. Dialogue isn’t prose.

Real people speak in fragments. Not in prose. Take this example:

BLAKE SNYDER’S CAT

Commander, we have forty-thousand alien ships that are starting to appear on our radar screens! They are coming in hot!

Reads great. But it’s too formal if you’re expecting someone to say it onscreen. For example, an animated cat.

So let’s improve it by breaking it into fragments, like how a real person (or cat) might say it, if they were under the same amount of pressure this cat appears to be under.

BLAKE SNYDER’S CAT

Commander! Radar screen. It’s lighting up. 40,000 alien ships inbound! Coming in hot!

“Radar screen” is a fragment. “It’s lighting up” is barely a complete sentence. “40,000 alien ships inbound” is a complete sentence, yes. But “Coming in hot!” is also a fragment. That’s how people talk. Be mindful and keep your ear focused.

Use contractions even if you don’t or didn’t or can’t

Real people tend to say “they’re” instead of “they are,” and “can’t” instead of “cannot,” and so on.

That’s because human communication, by and large, is like electricity, or water. That is, it tends to take the shortest route possible to the “ground,” in the case of electricity, or the “lower ground,” in the case of water. In other words, when most people speak (with the exception of all but the most fickle grammarians), they often blow past formality, either due to habit or in the name of expedience, in order to get their words out. They say things in the quickest way they can. Hence, contractions.

That said, you may want to avoid the overuse of contractions or blended, onomatopoeia-adjacent words in order to add ethic or regional flavor “C’mere, ya li’l jerk! I’m’a gonna slap your head right offa ya head.” That stuff gets real old, real fast, and contributes to reader fatigue.

Parentheses are for amateurs (angrily)

Parentheticals should only be used in moments when both (A) it’s absolutely essential that the reader understands that the line being spoken is read in a highly specific way, and (B) that highly specific way of speaking that line is not clear from the context.

So, for example, this…

Syd Field slams his fist against the wall.

SYD FIELD

(angrily)

I can’t believe you bought Save The Cat and not my book!

…is not a good use of parentheticals because it’s clear from the line above (Syd Field slams his fist against the wall) that Syd is angry. Therefore, it’s redundant to add (angrily) as a parenthetical.

Also bad: using parentheticals to convey action or description.

SYD FIELD

I’m writing a new book, and it’s all Screenwriting.

(Syd lights up a cigarette and loads his revolver)

And the people better love it.

Fie! All unacceptable. Don’t use parentheticals for this.

Here’s how to fix:

SYD FIELD

I’m writing a new book, and it’s about Screenwriting.

Syd lights up a cigarette and loads his revolver.

SYD FIELD

And the people better love it.

Kill your beatlings AKA don’t use (beat)

If there’s a moment in your screenplay’s dialogue when it’s absolutely mandatory that the reader understand that there’s supposed to be a (beat) there, and it’s not clear from the context that the speaker is taking that beat, then go ahead and use (beat). But use it sparingly.

Otherwise, let the actors and the director figure out where the pauses go.

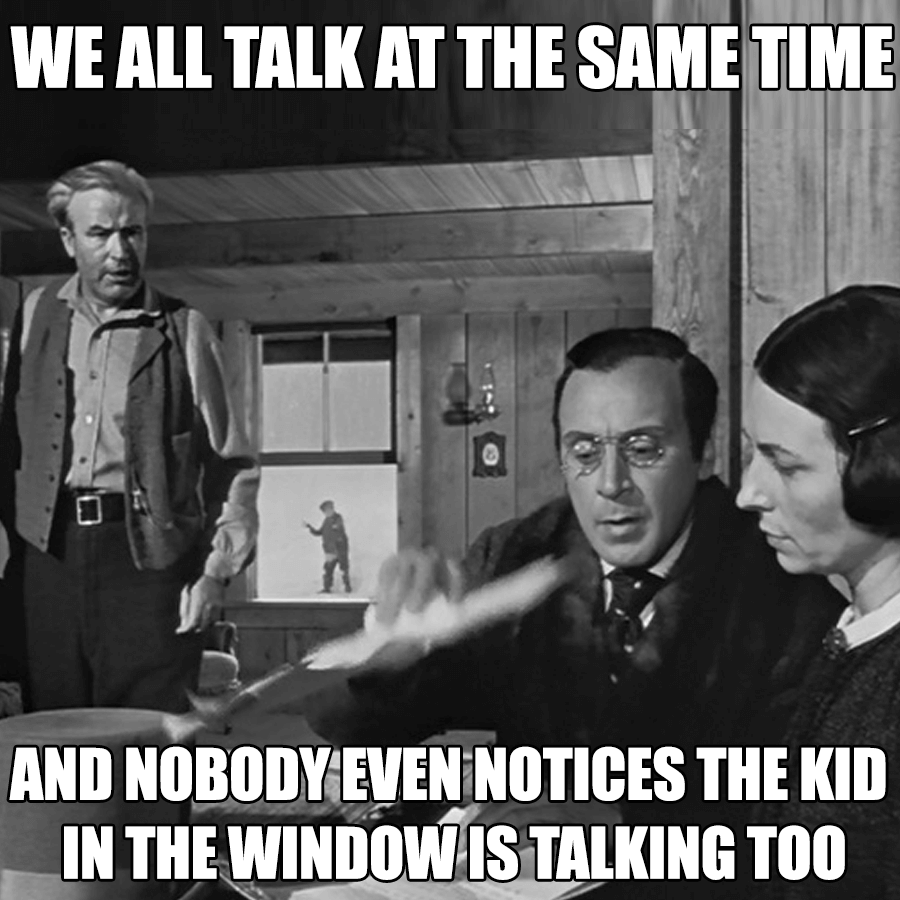

Overlap and interrupt your characters

Humans rarely wait for the other person to stop speaking before they themselves start to speak. Add realism to your dialogue by having characters interrupt each other, talk over each other, speak at the same time.

Use the Dual Dialogue feature available in most modern screenwriting apps to put two lines of dialogue from two different characters on the same spot on the page.

Have your characters cut each other off, finish each other’s sentences, and overlap just like real people do in real conversations.

Have your characters use non-sequiturs and/or take nonsensical turns

Every bit of text on the page of your screenplay should make sense, whether it’s action/description, a scene heading, or dialogue. That said, keep in mind that human beings often not only speak in fragments, but say things in a conversation that go nowhere, or aren’t clear, or might not make sense.

These moments, when rendered properly on the page, can be useful insofar as they could add up to the feeling that the character speaking is thinking things through, or not getting her head around something, or taking any number of different possible paths in her thought process during the conversation.

While a conversation must be clear on the page, if you can frame it and ground it well enough so that you don’t risk losing the reader, and if your characters are established well enough, you can actually pepper in quite a few of these oddball dialogue moments.

ROBERT MCKEE

I never thought I’d –

SYD FIELD

Thought you’d what?

ROBERT MCKEE

This whole thing is…

SYD FIELD

I don’t know what you’re getting at.

ROBERT MCKEE

Peanuts. Fine. Peanuts. Let’s just do this.

SYD FIELD

Write the book together?

ROBERT MCKEE

Yeah. Write the book. Let’s do it.

What does “peanuts” mean? Who cares? What thought is Robert having above when he leads with “I’d never thought I’d–” ? Who cares? The overall meaning of the conversation is clear. We get a bit of insight into Robert’s character because we see him thinking things through, or voicing concerns, even if the specific text of those thoughts or concerns don’t make perfect sense.

Differentiate your characters (AKA name them all LARRY)

Have you heard of this trick? Name all of your characters LARRY and then go through your script and see if you can tell their “voices” apart from one another.

If LARRY (your main character) sounds too much like LARRY (his wife), then you need to go make those two characters sound more distinct.

There’s nothing worse than scripts that drone on in the writer’s voice, despite the character changing from line to line. Keep your dialogue fresh and your characters discrete. Different voices add up to a chorus, with the potential of harmony. A single voice adds up to a long, boring single tone.